This post contains the most important piece of investment information you're likely to read this year. So that you can fully appreciate its worth, please briefly indulge me.

It's been six months since I began regaling you in these columns with my flamboyant opinions on our financial dog mess. I've ridiculed some politicians (well, I've gotta get a few laughs in somewhere), weighed in portentously on debt mountains, demographic implosions and deflation black holes, issued high-minded warnings about porked-out PIGS and contagion in China and compared our current economic torpor to a 21st century Zombie Dawn of the Dead.

But the world is not short on conflicting opinions and the greatest conflicts often seem to be between the world's smartest brains - so how to judge?

Nowhere is the difficulty of this more absurdly apparent than in the so-called science of economics, the only discipline in which two 'scientists' with directly conflicting theories once actually shared a Nobel Prize.*

*It happened, folks: Myrdal and Hayek, 1974.

Now don't get me started on economists. Suffice it to say that there are hundreds if not thousands of these poor stunted creatures across the world, fiddling away in their little cubicles with their Excel tables and their computer models and their prize-winning academic theories and, with a handful of honourable exceptions, none of them publicly predicted anything remotely like our current crisis, the most cataclysmic economic event in almost a century.

If an economist cannot even do that, what in the name of God is he for?

But it gets worse. Because, in an irony truly worthy of the description 'the blind leading the blind', many of these bozos are now closely advising the very world leaders upon whom our fate now depends.

Larry Summers (check that confident stare), as President Clinton's Treasury Secretary from 1999, blocked legislation which would have regulated the derivatives market (a prime contributor to the crash of 2008) and was instrumental in pushing through the Financial Services Modernization Act, an atrocity which finally swept away six decades of restrictions on the banking industry and freed them to indulge in many of the practices which led us to our current sorry pass. Speaking on that momentous day, he boasted: "Today, Congress voted to update the rules that have governed financial services since the Great Depression and replace them with a system fit for the 21st century."

Larry Summers (check that confident stare), as President Clinton's Treasury Secretary from 1999, blocked legislation which would have regulated the derivatives market (a prime contributor to the crash of 2008) and was instrumental in pushing through the Financial Services Modernization Act, an atrocity which finally swept away six decades of restrictions on the banking industry and freed them to indulge in many of the practices which led us to our current sorry pass. Speaking on that momentous day, he boasted: "Today, Congress voted to update the rules that have governed financial services since the Great Depression and replace them with a system fit for the 21st century." Where is he now, you justly ask? Behind bars? Why no, dear reader: in 2010, Larry Summers is Director of the White House National Economic Council, the chief advisor to President Obama.

Ben (he who sporteth a white beard so must be wise) Bernanke: isn't he the same Chairman of the US Federal Reserve who, in May 2007, two months before the subprime housing timebomb detonated, said: "The impact on the broader economy [of the problems in subprime] seems likely to be contained."...? With his esteemed colleagues on the Fed Monetary Policy Committee he then refused to slash interest rates as the crisis spiralled, only finally doing so after a huge market plunge put a gun to his head in January 2008.

Was he fired, you quite properly ask? Why no, dear reader, Ben Bernanke has just been re-appointed as Federal Reserve Chairman for a second term.

I can also happily inform you that both these august gentlemen are predicting, along with the broad consensus of world economists, a 'V'-shaped recovery accelerating through 2010.

Comforted?

Well then. If we can't trust the economists and we can't trust the politicians, is there an opinion we can trust? Is there any source we can turn to which has a reliable, documented, copper-bottomed long-term history of calling those major turning points? Of urging us to plough our money into riskier investments when times are looking up and warning us to take cover when the sky's about to fall?

Yes: amazingly, there is.

MR MARKET AND HIS

ASTOUNDING CRYSTAL BALL

Most people imagine that the stock market is a kind of shadow of what's really important: the economy. They assume quite understandably that if the economy is doing either well or poorly, the stock market follows.

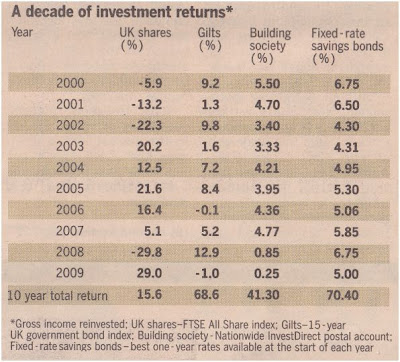

But what if the opposite is true? What if the economy is in fact being led by the stock market? Let's look back at 60 years worth of economic recessions and see what, if anything, the seemingly random ups and downs of the broad US S&P500 index can teach us:

Please click to enlarge

The grey bars represent recessions as determined by NBER, the official US arbiter of such things. This chart ends just before the latest recession, but the conclusion from looking at the evidence of the previous nine back to 1950 is unambiguous: the stock market does not follow the economy - it leads it, and by some margin.

With one exception (the steep, sudden recession of 1980), the market topped out on average five months before a recession officially started. What's more, it bottomed roughly four and a half months before it ended. The official end date of the latest US downturn has yet to be determined, but an edict has been issued regarding the beginning: December 2007. The stock market peaked two months earlier.

I mention this not because it necessarily enlightens us about where our money should go today but because it knees in the groin one of the most pervasive and foolish assumptions people have about the stock market: that it's just 'a lottery'.

In the long run, there is nothing random about the stock market. It reflects the sum of worldwide investor knowledge and expectations at any one time, the result of hundreds of billions of trading transactions in the language not of hot air and common opinion but of pounds, dollars and sense. It is a battle between the world's smartest brains for the cash of the world's dumbest investors, a fast-moving aerial dog-fight played out upon constantly shifting air currents of fear and greed.

Does that make it sound romantic? It ain't. It is Darwinian both for the stock and for the trader. If you cannot correctly judge the future prospects of the business you invest in, you die; if you cannot successfully anticipate the next move of your opponent - the other investors - you die.

The battle is therefore won by those who most successfully 'anticipate the anticipation of others'.

Does that make it sound romantic? It ain't. It is Darwinian both for the stock and for the trader. If you cannot correctly judge the future prospects of the business you invest in, you die; if you cannot successfully anticipate the next move of your opponent - the other investors - you die.

The battle is therefore won by those who most successfully 'anticipate the anticipation of others'.

That is why the stock market leads the economy; and that's why really smart investors try to figure out what leads the stock market.

--------------------------------

It ain't the economy,

IT'S THE CANDLESTICKS,

stoopid

stoopid

So far we've discussed the remarkable fact that the market is usually way ahead of both economists and the economy itself, and that, by definition therefore, finding a way to predict the overall direction of the market is a sure way to consistently forecast the general direction of the economy. And if we can do that, we can time many of the most essential investment choices we'll ever make.

Is that possible? Well there's no shortgage of predictive hot air. The world is stuffed with people telling us what the market ought to do. But what is it doing?

Is that possible? Well there's no shortgage of predictive hot air. The world is stuffed with people telling us what the market ought to do. But what is it doing?

Having a cocktail of opinions is all very well, but before tipping them down your gullet and backing them with hard cash, it usually pays to add a good strong shot of humility. And that's why I study charts.

STOCK CHARTS:

A LIVING MAP OF HUMAN GREED, FEAR AND FALLIBILITY

STOCK CHARTS:

A LIVING MAP OF HUMAN GREED, FEAR AND FALLIBILITY

An amazing number of pundits are sniffy about technical analysis, ranking it roughly on a par with psychic reading, astrology and tea-leaf divination. But traders know better. They know that chart patterns are not remotely random but serve as

- A shared map of the field of conflict, complete with battle lines and targets for attack and retreat, and

- An unblinking 200-year pictorial record of human economic progress and evolution, as represented by the most primitive of human behaviours, fear and greed

Gold chart, March 2010: A set of random marks on paper, or a battlefield between well-defined forces of fear and greed?

Go into any trading room in the City or Wall St and you'll be overwhelmed by the number of flickering chart screens, with hypnotized traders serviced by highly-paid charting analysts and technical strategists.

Indeed a certain hideous breed of investment nerd - the 'Quant' - has now proliferated throughout the financial services industry, its sole purpose being to identify and exploit mathematical probabilities unearthed by studying market behaviour.

Age-old investment strategies practised by the likes of famed investor Warren Buffett (find great companies, buy them cheap and hold their stock forever) now seem quaint and out-of-place in such a cold, automated, quantitatively-traded universe. Don't get me wrong, those time-tested strategies remain the benchmark. But this is how the likes of Goldman Sachs make money in 2010. And friends, if technical analysis is valued that highly in the hallowed halls of Goldman, it'll do just fine for me.

---------------------------

---------------------------

Now, I said I'd show you something special - and it's coming - but I need you to hang in there with me just a brief moment longer.

What we're exploring here is the possibility that, by focusing on a proven predictor of the economy - the stock market - there may be trustworthy technical clues which can help us see where both are likely to head over the long term. If there are, we would be able to rise above the conflicting chatter of economists, politicians, theorists and even the smartest individual investors, to see the true picture. Such a picture would give us a reliable and tremendously valuable head start in helping us make some of the most critical investment decisions of our lives.

With that tantalizing prospect in mind, then, let's take a brief look at one of the simplest types of analysis I use: one which, I've discovered, works extraordinarily well.

WHEN GOOD MARKETS GO

BAD

Study charts long enough and you discover something oddly comforting: when conditions get out of whack stock price behavior, made up as it is of decisions by flesh and blood human beings, remains highly predictable from one decade to the next. Extremes of fear and greed look pretty much the same in 2009 as they did back in 1929.

One market crash and recovery took place in 1929, one in 2009 -

can you tell which is which?*

Back in the summer of 2008, in those rose-tinted days before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, I was staring at a monthly chart of the Dow Jones Index and saw something most peculiar:

(Please open up the above chart and check the blurb, which will hopefully illuminate.)

It struck me that, since the appearance of just one of these 'low-hanging' price bars was a rare and often bullish event, two in succession might signify something twice as interesting.

So I checked back over eighty years of history. There were only seven precedents.

Five suggested a crash was dead ahead.

Five suggested a crash was dead ahead.

Although markets were becoming increasingly nervy in early September, nothing in the news made an imminent crash the most likely outcome. Still, I could not ignore the stark results of my study and sent the results in an email to one friend who was still invested in stocks:

Here's the first of those bullet points, a little local difficulty you might have heard about from the dim-and-distant 1930s:

Descent into the Depression - after two successive months (in red) spent sitting below the two-month average, the market recovered into mid-1930 - then began a 90% decline

At the same time as I was urging my friend to get out of the market, there were a plethora of star investors publicly exhorting us all to buy in. These included the Oracle of Omaha himself, Warren ('world's greatest investor') Buffett and our own Anthony ('the silent assassin') Bolton, for thirty years the most successful money manager in Britain. Perhaps if they had seen this humble little analysis they might have waited just a wee while longer before putting their millions to work, because less than three weeks later, this happened:

No, folks, that seemingly insignificant little chart pattern was anything but random: it depicted a market so weak it was incapable of rallying even under grossly over-sold conditions. The market had clanged a warning across the decades, clear as a bell, to anyone willing to hear.

*1929 on the left, 2009 on the right. The 1929 recovery failed at that point - stocks fell 90%.

------------------------

STOCK MARKET HISTORY

RARELY REPEATS,

BUT IT SURE AS HELL DOES RHYME

RARELY REPEATS,

BUT IT SURE AS HELL DOES RHYME

This is only the most dramatic example of many I could reel off in which a seemingly minor technical clue given off by markets portended a major move. For those willing to put money to work, paying attention to such clues can lead to major profits or, just as important, the avoidance of monster losses.

Again: when everything is stripped away what we are looking at is not some obscure technical process but the playing out of those basest of human emotions, fear and greed, which as we all know never change. That is what makes the study of past market behaviour during peaks and panics so reliable.

Research and experience suggest that the most powerful signals are those which, like the one shown above:

Research and experience suggest that the most powerful signals are those which, like the one shown above:

- Look back over decades of market behaviour

- Appear under the most extreme conditions

- Show a consistent set of outcomes which are

- Logically explicable in terms of investor psychology

Well, dear reader, I'm happy to say that all of these conditions apply to the chart I've dragged you through this technical hedge backwards to see. It is simple, un-varnished, exclusive as far as I know and is the closest thing to a crystal ball on the future of your current investments you're ever likely to see.

THE CHART OF THE CENTURY

Please right-click to enlarge in a separate tab or window

The above covers the period from 1977 to the present day, represented by the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Please also open the next chart in a new tab or window - it covers the years 1920 - 1948.

The monthly bars in red and white illustrate the movement of the Dow, which is tracked by the lower indicator in blue and magenta, called the Rate of Change.

ROC OF AGES

The Rate of Change (ROC) is one of the oldest and most widely-used measures of price momentum. It compares the closing price of the current month with the closing price x-number of months ago - in this case 10 months ago, which is standard. Wherever the line is rising above zero, the price is higher than it was 10 months before, and the higher the line rises, the more powerful the momentum of the move. Very, very rarely, the momentum lifts off the charts and may become so extreme that it simply cannot be sustained.

In December 2009, the Rate of Change reached 47.6 (the red horizontal line in the charts), its highest level since 1983. Prior to that, no readings as high had been registered since the Great Depression.

A very few readings have come within a whisker (two points) of the current peak, so I've included those to get a larger number of samples.** Let's look at them one by one, in reverse order, and examine what happened next in each case.

JUNE 1999: While the dot-com bubble went stratospheric in the Nasdaq, the broader stock market as represened by the Dow edged down a little before heading up to a final peak 7 months later. It then oscillated sideways for the following 8 months before finally rolling over into a major decline which lasted two more years.

Total loss peak-to-trough: 39%

JULY 1987: Managed one more month of gains before starting the slide which ended in the notorious Black Monday crash of October '87.

Total loss peak-to-trough: 42%

APRIL 1983: Edged down for 4 months, up to a slightly higher peak 3 months later, then sold off for 8 months before starting a strong recovery.

Total loss peak-to-trough: 17%

JANUARY 1939: Declined sharply for 3 months before rising gently to a marginally higher high 5 months after that. Then began a sideways crawl for 7 months leading to a major crash and a further decline lasting two years.

Total loss peak-to-trough: 41%

JANUARY 1936: Suffered a slight correction two months later but quickly recovered and surged to a brave new high 11 months after that. The market crashed immediately thereafter, wiping out all gains made over the previous year - and more.

Total loss peak-to-trough: 50%

APRIL 1933: Zoomed straight up to a peak 3 months later then oscillated sideways for 12 months, only barely reaching a new high. A strong recovery followed. The only example where prices never fell below the level of the first month of the study. However, in the middle of that period there was a:

Total loss peak-to-trough: 24%

NOVEMBER 1928: Rose for 2 months, fell for 2, then shot up to a peak 5 months later. That high was to last 25 years, as the market crashed immediately thereafter.

Total loss peak-to-trough: 89%

**Looking at the intervening years from 1950s to the '70s shows exactly the same dynamics but the extremes in the indicator were not so great, emphasizing the significance of the current reading. You can find a chart of that period in the Stocks section of this month's Investment Outlook.

DO NOT IGNORE THIS SIGNAL

The fact is that over the past century, this level of extreme momentum has appeared in one of only two circumstances: at the kick-off to the greatest bull market in history (1983) OR as a prelude to major crash events and bear markets (1928, 1936, 1939, 1987, 1999). The only other instance (1933) led to a four-year bull market - yet ALL the gains made in that advance were wiped out in a terrible crash and recession from 1937 - '42.

From a technical perspective, the level of the ROC is showing us that the market has used up pretty much all its gas. Any short-term (up to one year) gains from this point are virtually certain to be given back.

Why? Historically, stocks by this stage of an advance no longer seem so cheap and investors who have bought in start to zip up their wallets - just as sellers begin emerging from hibernation; the prospect of rising interest rates looms and with it a fear that the economy will not sustain its growth; and importantly, private investors remain on the sidelines: Joe & Jane Schmo, still bruised from the previous downturn, remain reluctant to jump in even after such a huge rally (don't forget, they've been hit by two big crashes in the space of a decade - not surprisingly then, the latest data continues to show that new money is flowing not into stocks but into supposedly 'safer' bonds). The problem is, Joe and Jane's participation is essential to fuel the next phase of the stock market advance.

What is most likely, then, is a period of one to two years when the market treads water before either breaking higher (thus signalling a genuine economic recovery) or lower (portending a probable double-dip).

We are either at the end of the beginning, or the beginning of the end, of this recovery.

Investors wondering whether to buy into renewed optimism - eg. take on a property, plough money into risky pension assets, buy stocks - would be wise to stay safe and await the verdict of the market, which will predict the overall direction of the economy, before making any long-term commitments. Because unless enough new buyers eventually emerge who see early evidence of a sustained recovery, as they did in 1983 or 1933, investors will get vertigo and the market and economy are certain to collapse.

------------------------

Friends, after six months of meandering, we finally have a clear map of the terrain. With the information above, this blog has now moved beyond the realms of speculation, bombast and light humour and passed well and truly into the danger zone where real money, property values, pension pots and hard won savings are at stake.

My own views on where we're headed are irrelevant in the face of such historical evidence. I've learned through experience to trust certain technical indicators over my own hunches or anyone else's 'expert' opinion. Indicators don't have a bullish or bearish bias; they aren't subject to fear, greed, complacency, selective memory or willful blindness and they cannot fall asleep at the switch; they aren't emotionally invested in any particular outcome and, unlike human financial advisors, they don't take a cut if they persuade you to invest on their advice; they are the best objective guide to the future we have - we just have to listen when they speak.

So if the market decides after a while that the economy is going to recover despite my conviction that it cannot, there's no point in me thumb-sucking about it. Bruising as it would be, I'll have to accept that my theories were simply mistaken, take it like a man and get on with making money.

But if I turn out to be right, some important decisions will soon have to be made: decisions about where we can most safely store our cash and how best to protect our pensions and investments in a worst-case scenario. Of course it will also represent a stupendous opportunity for those willing to put money on a falling market.

These prospects are what I'll begin to look at in this month's Investment Outlook, which you'll find posted below or in the archive section.

---------------------------

This has proved rather a sobering post to write, but next month I hope to rediscover my mirth as that great three-ring circus that is the UK General Election swings into town. Thanks as ever for reading, and do join me again from Sunday April 4th. Have a great month!