I thought it would be worthwhile looking back at the history of this much-mocked stock market indicator, since we now have at least two sightings of the Hindenburg Omen (and possibly three, depending on your definition of the rules) in the past two weeks, as well as several near-misses over the past few months.

For anyone who missed the recent media feeding frenzy and who has not yet caught my previous post, the Omen is a peculiar set of conditions which when found together seem to indicate a market on the verge of a nervous breakdown...

The rules were formulated back in the 1980s by a blind mathematician named Jim Miekka, who came up with a way to identify periods of divergent market breadth... a fancy term for what amounts to a stock market that looks both ways.

Stocks within an index should, in a healthy market environment, move pretty uniformly one way or the other; but on rare occasions they become highly polarized - a large number of stocks are failing and making new lows while others are simultaneously breaking out and hitting new highs. This makes the indexes highly unstable and vulnerable to a fall.

Miekka created a set of rules to identify this setup. Smart investors taking note of the indicator would be able to either exit the market before mayhem struck or position themselves to profit from a decline.

The original rules are as follows:

- That the daily number of NYSE new 52 Week Highs and the daily number of new 52 Week Lows must both be greater than 2.2 percent of total NYSE issues traded that day.

- That the NYSE 10 Week moving average is rising.

- That the McClellan Oscillator is negative on that same day.

- That new 52 Week Highs cannot be more than twice the new 52 Week Lows (however it is fine for new 52 Week Lows to be more than double new 52 Week Highs). This condition is absolutely mandatory.

(In recent years Miekka upped his requirement in rule 1 to 2.5%, but many afficionados still calculate it the original way and his alteration, while eliminating a couple of failed signals, has not materially improved the effectiveness of the indicator.)

NEVER MIND THE THEORY - DOES IT WORK?

Yes, grasshopper, it works. Since being formulated in the mid 1980s, the Hindenburg Omen has had a truly remarkable track record in identifying, at the very least, periods of unusually heightened risk in the market. It has never failed to warn of a major crash, and has predicted many of the most serious corrections.

Of the 44 signals documented below over a 45 year period, just 4 failed to register a decent, tradeable decline from the date of the Omen through the next three months. Sometimes you had to wait for it to show up, but if you were looking to go short the fall was usually worth the wait.

11 of the 44 Omen 'clusters' (two or more instances close together) have appeared right before a market crash (defined as a decline of at least 15%). So while a crash is only a 25% probability on the evidence of these precedents, the risks are greater than random by many orders of magnitude.

The Omen popped up in 1999 and 2000 just before the dot-com bust which took 50% off the Dow and 75% off the Nasdaq; in summer 2007 it showed up as the financial crisis was looming - foreshadowing a 58% wipeout of the S&P500 and a halving of the FTSE100.

We've now seen another cluster of Hindenburg Omen observations, in August 2010.

THE CATALOGUE OF CARNAGE

For ease of historical comparison and research, I've decided to take a snapshot of cluster observations since 1965 and present them here.

The visual evidence reveals that, while downside risks are indeed substantial over the next several months, there is an additional risk worth noting of an upside surprise - especially in the short term.

I derived the dates from two sources. First, a recent study of the indicator by noted analyst Jason Geopfert of Sentimentrader.com. It seems extraordinary, but even in today's highly-computerized environment, data for New Highs and New Lows varies between different information providers resulting in Jason's dates occasionally differing from others.

For completeness, therefore, I also include additional dates from 1985 onwards which have been identified by Robert McHugh of Main Line Advisors. McHugh has followed and researched the Omen in more detail than most and bases his identifications on data from the Wall St Journal.

There's some consensus that individual occurences of the Omen are less reliable than those which come in clusters. Jason (whose site and analysis I thoroughly recommend) identified every instance since 1965 where either two Omens occured within a two-week window, or three occured within a thirty-day window - both of which conditions apply in August 2010.

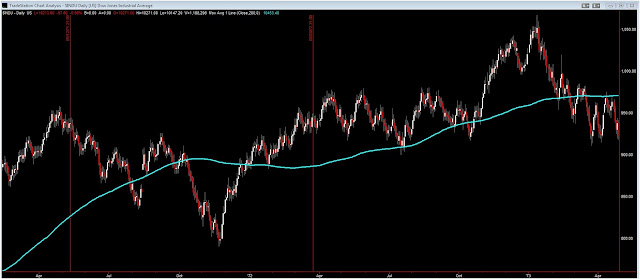

McHugh requires two occurences within a 36-day window (I've charted his observations separately and marked them with an asterisk* - also note that the dates he has provided are those of the initial Omen observation, even when several more subsequently followed). I've plotted all these against the Dow Jones Industrials Average for consistency.

I hope you find these charts useful; check out a couple of thoughts I had on trading the signals at the end of the following Hindenburg 'Catalogue of Carnage'.

1965

1967

1971-1972

1974

1978

1979-1980

1986

1987

1990

1991

1994

1995

1998

1999

2006

2007

CONCLUSION:

ON TRADING THE HINDENBURG OMEN

You can see that, while most instances led to declines within the next several weeks, it was not a risk-free ride for traders who planned to sell short. Sudden moves higher were quite common, certainly in the short term. I have three observations which might help:

- Excluding those which failed completely (see below) every single Omen signal originating ABOVE the 200-day simple moving average (turquoise line in the charts) saw the market fall and test that 200 DMA at some point over the next three months. Some went on to drop below the average, while many reversed at that point. One possible plan to limit risk would be to take profits at the 200DMA, reinvesting them only on a further breakdown.

- Signals which occured on or just BELOW the 200DMA (the situation we find in August 2010) were vulnerable to a violent reversal higher. Stops placed at nearby resistance in the zone slightly above the 200DMA allow for a little wiggle-room (eg. see 2001), but insure against a sudden burst higher taking you out.

- 4 signals failed completely - ie. the market went more or less straight up and did not fall more than fractionally below the close of the observation day during the next three months - a 10% failure rate which is not to be dismissed lightly. Placing stops above the most recent market high is therefore a sensible way to ensure you don't get creamed. Occasionally declines materialize in the longer term but the market shoots higher in the short term - taking out any stops you might have placed above recent highs (eg. see 2006, 2007). If that happens I'd use an indicator such as the MACD to alert me should the market subsequently stall out at a higher level (even better!) and be prepared to re-enter my short positions on any further weakness.

BEST OF LUCK!